Il Blog

How I discovered then translated Fabrizio De Andrè

by Dennis Criteser on January 9, 2015

Ready for a confession from a music lover and an Italian? I know very little about Fabrizio De Andrè, one of the most legendary Italian singer/songwriters ! However, if you’re not Italian, you’re excused, and luckily today’s guest post will help fill in that gap. I’m a firm believer that music and languages go hand in hand, “vanno a braccetto”! Buona lettura, Mirella

When my family decided to go to Italy in 2008, my daughter was several years into a deep enthrallment with Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, and especially with the 1968 Franco Zeffirelli film version. Indeed, our trip to Italy was a pellegrinaggio – a pilgrimage. We arrived in Venice and headed for a weeklong stay in Verona. For many travelers to Italy, La Casa Giulietta and La Tomba di Giulietta may be somewhat cheesy tourist destinations, but for my daughter they were churches, power spots suffused with magic and deserving of multiple extended visits so she could be surrounded and entranced by the charge from that story of so long ago.

When my family decided to go to Italy in 2008, my daughter was several years into a deep enthrallment with Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, and especially with the 1968 Franco Zeffirelli film version. Indeed, our trip to Italy was a pellegrinaggio – a pilgrimage. We arrived in Venice and headed for a weeklong stay in Verona. For many travelers to Italy, La Casa Giulietta and La Tomba di Giulietta may be somewhat cheesy tourist destinations, but for my daughter they were churches, power spots suffused with magic and deserving of multiple extended visits so she could be surrounded and entranced by the charge from that story of so long ago.

In preparation for our voyage, my daughter and I spent six months building basic Italian skills with Rosetta Stone. We were able to say simple things, and could sometimes even understand the replies! Following our glorious trip (which also included visits to Mantua, whereto Romeo had been banishéd, and to Toscania where Zeffirelli had filmed the wedding and death scenes), it was time for my daughter to choose a language for study in school. It could be nothing other than Italian. But her school didn’t offer Italian, so we arranged for independent study, and I tagged along for the ride.

Enter Mirella Colalillo. We found Mirella online, then teaching out of Toronto, and proceeded with weekly Skype lessons for two years.

I spent many of my younger years in serious pursuit of music and ended up as program director for a music school in San Francisco. With fatherhood, though, most of my music playing had been set aside. Given my background, Mirella of course sent me some links of Italian musicians to check out. I clicked on the first link and was taken to a song called “L’unica cosa” by Marta sui Tubi. On first listen I thought it was not quite to my tastes, though it had a fun sense of humor. I was going to return to her email and click on the next link when something drew me back for a second listen. Like a revelation, that two minutes and thirty seconds made me feel excited about music in a way I hadn’t felt for decades. I immediately began exploring their other music on YouTube and became, without a doubt, their biggest fan outside of Italy, and for all I know their biggest fan in the world!

Marta sui Tubi single-handedly rekindled my engagement with music. As I continued to study Italian alongside my daughter, I began to explore the world of Italian cantautori. One of the artists I listened to was Fabrizio De Andrè, who is sometimes called the Bob Dylan of Italy. He didn’t immediately grab me as did other great songwriters like Lucio Dalla and Giorgio Gaber, but as I listened more, and in particular as I paid attention to his lyrics, I became ever more impressed with the body of work he created over almost forty years of writing.

With my reawakening to music, I picked up my guitar again, inspired to learn some of the new songs I was listening to, just as I’d done in my younger years. My skills as a singer and guitarist lined up best with the songs of De Andrè, so I was drawn deeper into his musical world. And because Fabrizio De Andrè wrote not only about love but also about politics, social affairs, history and literature, I also learned about many aspects of Italian culture.

I now have a trio that occasionally performs De Andrè songs at the Museo Italo-Americano in San Francisco. And I was inspired to translate all of De Andrè’s songs into English in a way that would do them justice. I’ve just published these translations online – along with background information on each song and album – at deandretranslated.blogspot.com. It’s my hope that the site will be a resource for one of the world’s great singer/songwriters to become appreciated more fully outside of Italy.

Grazie mille, Mirella – my musical rinascimento began with you!

Dennis Criteser is Program Director of Blue Bear School of Music in San Francisco and has been studying Italian since 2008. An erstwhile singer/songwriter with eight albums to his credit, he is now happily exploring Italian pop music and has just completed translating the songs of Fabrizio De Andrè.

Dennis Criteser is Program Director of Blue Bear School of Music in San Francisco and has been studying Italian since 2008. An erstwhile singer/songwriter with eight albums to his credit, he is now happily exploring Italian pop music and has just completed translating the songs of Fabrizio De Andrè.

Do you have any favourite De Andrè songs? If you do, don’t forget to share them in the comments below! And if you don’t check out Dennis’s blog!

Auguri speciali with my Italian animated videos

by Mirella Colalillo, December 19, 2014

(English Follows)

Il tempo vola! Sono tornata in Italia all’inizio di ottobre e il Bel Paese mi ha regalato il clima invernale più mite che avrei mai potuto sognare. In puro stile italiano ho mangiato, appena raccolti dall’orto di mio padre, tanta frutta e verdura, ho fatto viaggi a Roma, Torino e in magici paesini sconosciuti. Ho anche contemplato le nuvole durante i temporali e dopo il funerale del mio caro zio, un promemoria per apprezzare ogni momento, e amare sempre al massimo.

In tempi come questi la mia creatività raggiunge il picco, quindi sono molto felice di presentarti il mio canale YouTube dove creerò animazioni in 2D e 3D, una delle mie passioni, in combinazione con la lingua italiana. Spero che ti piaceranno!

Il mio primo video è un semplice Augurio Natalizio per ringraziarti del tuo appoggio e per augurarti tutta la felicità che meriti. Credo che a qualsiasi età e ovunque ci troviamo nella vita, i sogni possono diventare realtà!

Con Affetto,

Mirella

Il tempo vola! Time flies…I’ve been back in Italy since the beginning of October and il Bel Paese has gifted me with the mildest winter weather I could dream of. In pure Italian style I’ve been eating, fresh from my Dad’s vegetable garden, orto, lots of vegetables and fruits, enjoyed trips to Roma, Torino and to magical unknown towns. I have also been contemplating the clouds during rain storms, and after the funeral of my dear uncle, a reminder to appreciate every moment, and to always love to the fullest.

In times like these my creativity peaks so I’m very happy to present to you my YouTube channel, where I’ll be creating animations in 2D and 3D, one of my passions, in combination with teaching Italian. I hope you enjoy them!

My first video is a simple Holiday Greeting to thank you for your support and to wish you all the happiness you deserve. I believe that at any age and anywhere you are in life, dreams can come true!

With Love,

Mirella

~~~

From LA BELLA LINGUA to MONA LISA

by Dianne Hales on August 25, 2014

In this guest post Dianne Hales, author of “La Bella Lingua”, tells us how her new book about La Bella Mona Lisa came to life. At the end of the post you can challenge your knowledge of Mona Lisa with a little quiz that Dianne and I have created for you.

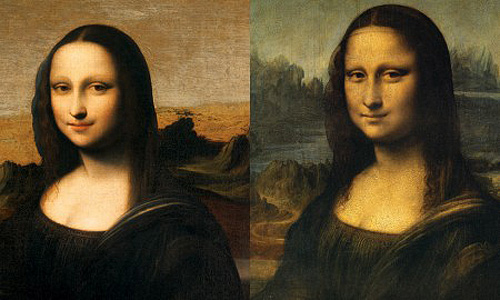

“Earlier Version” and the Louvre Mona Lisa – courtesy of the Mona Lisa Foundation

Her name seduced me. The first time that I heard “Mona (Madame) Lisa Gherardini del Giocondo”— many years after I first beheld Leonardo’s portrait in the Louvre — I repeated the syllables out loud to listen to their Italian sounds. Immediately I felt a surge of curiosity about the woman everyone recognizes but hardly anyone knows.

After falling—happily, gladly, giddily—in love with Italian many years ago, I became just as enamored with the life and times of a true Fiorentina, a daughter of the Renaissance, a merchant’s wife, a loving mother, an artist’s muse and, in her husband’s words, “a noble spirit.” Somehow it seemed only natural to go from a passion for la bella lingua to a quest for una bella donna.

On the trail of Lisa’s story, I followed facts wherever I could find them. I sought the help of authoritative experts in an array of fields, from art to history to sociology to women’s studies. I delved into archives and read through a veritable library of scholarly articles and texts. And I relied on a reporter’s most timeless and trustworthy tool: shoe leather. In the course of extended visits over several years, I walked the streets and neighborhoods of Mona Lisa’s Florence, explored its museums and monuments and came to know—and love—its skies and seasons.

Mona Lisa, I discovered, was a quintessential woman of her times, caught in a whirl of political upheavals, family dramas, and public scandals. Descended from ancient nobles, she was born and baptized in Florence in 1479. Wed to a truculent businessman twice her age, she gave birth to six children and died at age sixty-three in 1542.

Mona Lisa’s life spanned the most tumultuous chapters in the history of Florence, decades of war, rebellion, invasion, siege — and of the greatest artistic outpouring the world has ever seen. Her story creates an extraordinary tapestry of daily life in a vibrant city bursting into fullest bloom.

Five centuries after Mona Lisa Gherardini’s death, the world remains eager to learn more about her. Amazon.com chose my book, Mona Lisa: A Life Discovered, published by Simon & Schuster, as one of the “best books of the month” for history and for biography and memoirs. BBC read episodes on the radio for its “Book of the Week” program. CNN and USA Today selected it as one of their “hottest reads” of the summer. Reviewers have praised it as “entertaining,” “enthralling,” “vivid and accessible” and “lyrical.” BRIDES magazine included it on its list of “10 most-read books for your honeymoon.” “Anyone who loves Italy and art—and who doesn’t?—will adore this book,” predicts Frances Mayes, author of Under the Tuscan Sun.

I hope that all of you who love Italian will enjoy this new journey of discovery!

Dianne Hales

Dianne Hales is a prize-winning, widely published journalist and the author of MONA LISA: A Life Discovered. In recognition of her previous book, La Bella Lingua: My Love Affair with Italian, the World’s Most Enchanting Language, as “an invaluable tool for promoting the Italian language,” the President of Italy conferred on Dianne the highest honor its government can bestow on a foreigner, the title of Cavaliere dell’ Ordine della Stella della Solidarietà Italiana (Knight of the Order of the Star of Italian Solidarity.)

Dianne Hales is a prize-winning, widely published journalist and the author of MONA LISA: A Life Discovered. In recognition of her previous book, La Bella Lingua: My Love Affair with Italian, the World’s Most Enchanting Language, as “an invaluable tool for promoting the Italian language,” the President of Italy conferred on Dianne the highest honor its government can bestow on a foreigner, the title of Cavaliere dell’ Ordine della Stella della Solidarietà Italiana (Knight of the Order of the Star of Italian Solidarity.)

You can follow her prize-winning blog on Italy’s language and culture at www.becomingitalianwordbyword.typepad.com and new blog on discovering Mona Lisa at www.monalisabook.com

QUIZ:

Pronti? Via!10 Facts You May Not Have Known about Mona Lisa

Join the ITALIANO ALLA MANO club for weekly study plans, learning materials and tips:

Pronunciation Tip #2: “Italian Tongue Twisters”

Suggerimento di pronuncia n. 2: “Scioglilingua italiani

(English follows)

Parlare oscuramente lo sa fare chiunque, ma chiaro pochissimi – Galileo Galilei

(Everyone knows how to do speak obscurely, but very few can speak clearly.)Galileo Galilei, Considerazioni al Tasso, 1589

Non potrei essere più d’accordo con Galileo, ed è per questo che gli scioglilingua, parola che è già di per sé uno scioglilingua, sono utili, almeno per quanto riguarda la parte tecnica del parlare!

È interessante notare che in italiano “scioglilingua” significa letteralmente “sciogliere la lingua”. Suppongo che aggrovigliando la lingua attorno a lettere e suoni alla fine s’impara ad allentarla e a non “attorcigliarsi” più.

In effetti, “gli scioglilingua” ti aiutano a migliorare la dizione, e non c’è da meravigliarsi, che i professionisti alla radio o nei film usino gli scioglilingua per migliorare le loro capacità oratorie o per riscaldarsi prima di esibirsi.

Uso gli scioglilingua per i seguenti motivi:

1) per migliorare la scorrevolezza nel parlare,

2) per ridurre e rimuovere accenti e inflessioni,

3) per parlare con più sicurezza e rilassarsi,

4) per divertimento: quello che dici non deve per forza avere senso!

Ogni lingua ha specifici scioglilingua che attivano suoni o parole che provocano lo scioglimento della lingua! In italiano, ad esempio, molti scioglilingua mettono alla prova la capacità di pronunciare suoni vocalici aperti e chiusi. Alcuni scioglilingua sono molto utili per lettere specifiche con cui gli studenti di italiano hanno difficoltà, come “R”, “T”, “S”…

Qui troverai 4 “scioglilingua”, a 2 velocità. La velocità 1 è un riscaldamento, la velocità 2 è dove lasci la tua zona di comforto e non ti preoccupi dei risultati, che arriveranno con pazienza e pratica … stanne certo/a!

Buon divertimento!

I couldn’t agree more with Galileo, and that’s why tongue twisters, “gli scioglilingua”, a word that is already a tongue twister in itself, are useful, at least as far as the technical speaking part goes!

It’s interesting to notice that in Italian “scioglilingua” literally means “tongue loosener”. I suppose that by twisting your tongue around letters and sounds you will eventually learn to loosen it and no longer stumble on a word, “inciampare in una parola.”

In fact, “gli scioglilingua” help you improve your speaking and your pronunciation, and it’s no wonder, “non c’è da meravigliarsi”, that professional speakers on the radio or in films use tongue twisters to improve their speaking skills or to warm up before they perform.

I use tongue twisters for the following reasons:

1) to improve speaking fluidity

2) to reduce and remove accents and inflections

3) to increase confidence and loosen up when speaking

4) for fun — what you say doesn’t have to make sense!

Every language has specific tongue twisters that trigger sounds or words that cause tongue twisting! In Italian, for example, many tongue twisters challenge your ability to pronounce open and closed vowel sounds.

Some tongue twisters are very helpful for specific letters that students of Italian have a difficult time with, such as “R”, “T”, “S”,…

Here you’ll find 4 “scioglilingua”, in 2 speeds. Speed 1 is a warm up, speed 2 is where you leave your comfort zone and don’t worry about the results, which will come with patience and practice… stanne certo! (you can stay assured!) Buon divertimento!

Tigre intriga tigre

speed 1

speed 2

particolareggiatissimamente (la parola più lunga registrata in italiano / the longest registered word in Italian)

speed 1

speed 2

Date del pane al pazzo cane, date del pane al cane pazzo (attenti a non scambiare la “p” con la “c” / be careful not to turn the “p” into a “c”!)

speed 1

speed 2

Questa e’ molto popolare / This is a very popular one: Sopra la panca la capra campa, sotto la panca la capra crepa

speed 1

speed 2

It means…: “Over the bench the goat lives, under the bench the goat dies.”

….“senza senso”, meaningless! 🙂

Più fai pratica e più noterai “la lingua che si scioglie”.

Fammi sapere nei commenti qui in basso quali suoni trovi più facili o più difficili da riprodurre!

The more you practice the more you’ll notice “la lingua che si scioglie”, your tongue loosening up.

Let me know in the comments below which sounds you find the easiest or hardest to reproduce!

A presto!

Mirella

Improve speaking and grammar while learning some Italian jokes!

How to use idiomatic expressions formed by “avere” and “essere”

by Mirella Colalillo on May 3, 2014

It’s well-known by now, “è risaputo ormai”, that Italians are the leaders not only in delicious food, fashion, cultural treasures, but also in expressing feelings, sensations, and opinions. From happiness to dissatisfaction and everything in between.

If you run into your Italian friend and ask her how she is doing, forget about “I’m good, and you?” for an answer, and instead, prepare for a detailed description of “vita, morte e miracoli”, as we say in Italian. If you don’t want to be labeled as “antipatico/a”, I suggest you follow along and do the same. At worst, “male che vada”, you might end up enjoying yourself “al bar”, at the coffee shop. And let’s be honest, going for your daily jog in the park and rushing to update your Facebook, Twitter, “e chi più ne ha più ne metta”, and so on and so forth status can wait anyway.

“Ascoltare. Non c’è cosa migliore da fare che ascoltare chi ha qualcosa da dire” @parlate_it

(Tweet-worthy!)

(Translation: “To listen. There is nothing better to do than to listen to someone who has something to say.”)

The best way to make a good impression, “fare una bella figura”, is to learn the most common idiomatic expressions in Italian that use “avere” (to have) and “essere” (to be), which, as many of you have complained “all’italiana” (Italian style), do not correspond to the English expressions. For example: “Io ho sonno” (I’m sleepy), “Io sono stanco” (I’m tired).

Avere + noun is used in many idiomatic expressions in Italian, but the equivalent English expressions are generally formed with essere + adjective.

There is no specific rule that explains this difference. The best advice is to:

- first learn the conjugations of the verbs “essere” and “avere” starting with il “presente indicativo”

- then learn each expression correctly

- and as always practica, pratica, pratica!!

Here are some idiomatic expressions in Italian that use “avere” and “essere”.

“Avere” is used in the following expressions:

avere caldo – to be hot

avere freddo – to be cold

avere fretta – to be in a hurry

avere paura – to be afraid

avere bisogno di – to need

avere voglia di – to want, to feel like

avere a che fare con – to deal with

avere sete – to be thirsty

avere sonno – to be sleepy

avere fame – to be hungry

“Essere” is used in the following expressions (just like in English!):

essere stanco/a – to be tired

essere arrabbiato/a – to be angry

essere contento/a – to be happy

essere annoiato/a – to be bored

essere felice (m/f) – to be happy

essere triste (m/f) – to be sad

essere entusiasta (m/f) – to be enthusiastic

essere preoccupato/a – to be worried

essere in ritardo – to be late

essere testardo/a – to be stubborn

Allora, come sto?

Oggi sono felice e ho voglia di fare una passeggiata. Non ho freddo, perché è finalmente arrivata la primavera in Canada! Sono molto entusiasta!

(How am I? Today I am happy and I feel like taking a walk. I’m not cold, because spring has finally arrived in Canada! I’m enthusiastic!)

E tu come stai? Let me know in the comments below.

Remember there is no quick fix in learning idiomatic expressions… practice makes perfect!

If you liked this post please share & like!

Grazie,

Mirella

Popular posts:

Pronunciation Tip #1: “Practice Italian with a flawless speaker!”

Imagine learning lots of grammar and vocabulary only to discover that listeners find it hard to understand what you say…è terribile per la comunicazione!

Also, if you can’t pronounce a word correctly, then you may not be able to hear it when spoken by another person either… ancora più terribile per la comunicazione!

This is a very common problem so don’t fret (non ti allarmare). I put together 7 solutions to improve your pronunciation based on my experience teaching Italian and learning languages.

In this post I’ll share my 1st tip: “Practice Italian with a flawless speaker!”

“Learning proper Italian from the start saves you time and frustration later correcting what you’ve learned incorrectly.”

It can sometimes be very difficult to correct what you’ve learned incorrectly as it turned out for my friend who had a teacher in elementary school that was very passionate about English, but was hardly proficient enough to teach simple words, such as “apple”, which sounded more like “apele” (similar to the word “ape”, “scimmia” in Italian), although she knew all the grammar. Till this day, over 20 years later, my friend still struggles to pronounce “apple” properly.

His English teacher, also a relative of mine in my little town, wanted to share her passion and land a job, but teaching is a serious matter. When I started teaching English in Italy, although I had reached the advanced level C2, according to the “Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment”, I felt it would be fair to teach only levels A and B since I wasn’t speaking English on a daily basis and wouldn’t be able to teach successfully at a higher level.

Improvised language teachers are not a good deal!

So how do you know if a teacher speaks proper Italian?

Talk and listen to them a bit before jumping into it and, depending on whether the teacher is a native speaker or a non-native speaker, the pronunciation issues, if there are any, will differ.

I would ask both if they have any particular accents or regional intonation, hoping they’re aware and honest!

However, to be certain, I would go ahead and look out for more specific issues….

In the case of the native speaker pay attention to:

- how they pronounce the grave or acute vowels such as in the words “verde” (the “e” is acute “vérde”), “cosa” (the “o” is grave “còsa”);

“verde” correct:

- whether they tend to pronounce single consonants as double consonants instead; an example is “amore” sometimes mistakenly pronounced with a double “m” (the“o” is acute);

“amore” correct:

- whether they shorten the infinitives stressing the last vowel, like “mangià” instead of “mangiare”, “parlà”, instead of “parlare”, and so on;

While you’re at it, you can also check some grammar, which will give you a better idea of their speaking accuracy:

- how they say: “I hope you are well.” (correct: “spero che tu stia bene”),

- how they say: “Can you speak Italian?” (correct: “sai parlare l’italiano?” – not ‘puoi’ parlare l’italiano?”);

In the case of the non-native speaker, issues usually concern:

- pronouncing the vowels,

- stressing the words correctly,

- pronouncing the “r”, the “t”, the “sch”, double consonants,

- pronouncing the vowels at the end of the words and pronouncing them correctly (they are not all acute, only the ones with accents on them).

A way to verify that they are flawless speakers is to find a short audio snippet and ask them to repeat it. You can find excellent and reliable audio from Italian language manuals.

“Speaking properly is a form of respect for a language.”

Let me know in the comments below what your experience has been learning Italian.

Stay tuned for my next tip about my favourite language sharpener!

If you liked this post please share & like!

Grazie,

Mirella