(English follows)

Da Città intelligenti a Villaggi intelligenti

In Europa si discuteva già nel 2015 di una ridistribuzione della popolazione presso le zone rurali. Il fenomeno della deurbanizzazione dei borghi accomuna tutto il Vecchio Continente. La tematica però ha assunto maggiore rilievo nel 2020 con l’incremento dello slow tourism, il turismo lento, e del turismo locale. Durante il lockdown si è parlato molto di città intelligenti, smart city, soprattutto quando si attendeva il ritorno alla vita sociale e cittadina. Il dibattito si sposta adesso in periferia. Vediamo che dopo le città, anche borghi e paesini diventano “smart” e prendono il nome di smart village, villaggi intelligenti, ossia borghi e paesini in cui sostenibilità e riqualificazione si incontrano e creano benefici su diversi livelli.

Da un lato secondo gli esperti bisogna iniziare a rendere più autonomi i paesi, dall’altro progettare una decrescita della città. Rivitalizzare le aree rurali e le comunità invece di costruire ex novo, riqualificando ciò che già è presente nel luogo.

Gruppo tematico sui Villaggi intelligenti

Un gruppo tematico (WG) ha analizzato questo argomento dei “Villaggi intelligenti” da settembre 2017 a luglio 2020. Ha esplorato idee e iniziative per rilanciare i servizi rurali attraverso l’innovazione digitale e sociale. Ha esaminato soluzioni per potenziare e rendere più sostenibili i servizi rurali, quali ad esempio la sanità, i servizi sociali, l’istruzione, l’energia, i trasporti o il commercio al dettaglio, grazie all’impiego delle tecnologie dell’informazione e della comunicazione (TIC) e a progetti e azioni locali di tipo partecipativo.

Si è concentrato anche sulla produzione e distribuzione locale di energia alternativa, diminuzione dell’impatto ambientale nel settore alimentare (attraverso la valorizzazione della produzione locale del cibo), e mediante la diminuzione del consumo di suolo.

Ha definito una guida pratica sull’utilizzo di tutti gli strumenti strategici atti a favorire la nascita e lo sviluppo di villaggi intelligenti. Inoltre ha creato un collegamento tra le varie iniziative in corso, che dimostrano il crescente interesse che questo tema suscita a tutti i livelli.

Il primo esempio di Villaggio intelligente

Il primo villaggio intelligente nasce in un borgo toscano che conta poco più di 2500 residenti. Il borgo di Santa Fiora sul Monte Amiata, in provincia di Grosseto ha messo a punto nel 2021 un progetto per trasformarsi nel primo villaggio Intelligente d’Italia. Non solo c’e’ la banda ultralarga per una connessione efficiente e veloce, ma persino un servizio di bici elettrica. Inoltre non mancano l’idraulico e il muratore a domicilio e la possibilità per le famiglie, di assumere una delle baby sitter messa a disposizione da una cooperativa locale. Da un loft si gode della vista dell’affascinante peschiera, voluta dagli Aldobrandeschi per convogliare l’acqua del monte Amiata.

“L’esperienza del Covid-19 – spiega il sindaco di Santa Fiora, Federico Balocchi – ci ha costretto a rivedere l’organizzazione del lavoro sperimentando su larga scala lo smart working. Alcune strutture turistiche d’Italia hanno colto questa opportunità con un’offerta su misura per il lavoratore che cerca un ambiente rilassante, al mare o in montagna. Nel caso di Santa Fiora è un intero comune che si propone come smart working village”. “Crediamo, infatti – aggiunge Balocchi – che il lavoro da remoto, non sia solo una soluzione temporanea per affrontare l’emergenza, ma possa rappresentare il futuro, almeno per certe professioni, mettendo in modo intelligente la persona nella condizione di operare al meglio per la propria azienda e al tempo stesso di essere felice, senza dimenticare che stare bene significa anche essere più produttivi. Con il bando vogliamo offrire un incentivo per stimolare questo tipo di scelta, ma ovviamente l’auspicio è che dopo un periodo di prova, per alcuni Santa Fiora diventi una scelta permanente venendo a vivere definitivamente qui con la famiglia”.

Il vantaggio dei paesi è quello di contenere una comunità in grado di cooperare più facilmente. Infatti la differenza tra villaggi intelligenti e città intelligenti va al di là del potenziale sostenibile e digitale.

Ti piacerebbe vivere in un villaggio intelligente?

English version

From Smart Cities to Smart Villages

In Europe there was already discussion in 2015 of a redistribution of the population in rural areas. The phenomenon of the deurbanization of the villages unites the entire Old Continent. The issue, however, took on greater importance in 2020 with the increase in slow tourism, turismo lento, and local tourism. During the lockdown there was much talk of smart cities, città intelligenti , especially when the return to social and city life was expected. The debate now moves to the suburbs. We’ve seen that after the cities, even villages have become “smart” and are called smart villages, villaggi intelligenti, where sustainability and redevelopment meet and create benefits on different levels. On the one hand, according to experts, we need to start making the villages more autonomous, on the other, planning a decrease in the city. Revitalizing rural areas and communities instead of building from scratch, therefore redeveloping what is already present in the place.

Thematic Group on Smart Villages

A thematic group (WG) analyzed this “Smart Villages” topic from September 2017 to July 2020. It explored ideas and initiatives to revive rural services through digital and social innovation. It explored ways to enhance and make rural services more sustainable, such as health, social services, education, energy, transport or retail, through the use of information and technology technologies. communication (ICT) and community-based local projects and actions.

It also focuses on the local production and distribution of alternative energy, reduction of the environmental impact in the food sector (through the enhancement of local food production), and through the reduction of land consumption.

It has defined a practical guide on the use of all the strategic tools aimed at favoring the birth and development of smart villages. It has also created a link between the various ongoing initiatives, which demonstrate the growing interest that this topic arouses at all levels.

The first example of an intelligent village

The first intelligent village was born in a Tuscan village that has just over 2500 residents. The village of Santa Fiora on Monte Amiata, in the province of Grosseto developed a project in 2021 to become the first Intelligent village in Italy. Not only is there ultra-broadband for an efficient and fast connection, but even an e-bike service. There is also no shortage of plumbers and bricklayers and the possibility for families to hire one of the babysitters made available by a local cooperative.

From a loft you can enjoy the view of the fascinating fish pond, commissioned by the Aldobrandeschi to convey the water of Mount Amiata.

“The experience of Covid-19 – explains the mayor of Santa Fiora, Federico Balocchi – forced us to review the organization of work by experimenting with smart working on a large scale. Some tourist facilities in Italy have seized this opportunity with a tailor-made offer for the worker looking for a relaxing environment, by the sea or in the mountains. In the case of Santa Fiora it is an entire municipality that proposes itself as a smart working village “. “We believe, in fact – adds Balocchi – that remote work is not only a temporary solution to deal with the emergency, but can represent the future, at least for certain professions, intelligently putting the person in the condition to work at their best for your company and at the same time being happy, without forgetting that feeling good also means being more productive. With the announcement we want to offer an incentive to stimulate this type of choice, but obviously the hope is that after a trial period, for some Santa Fiora will become a permanent choice by coming to live here permanently with the family “.

The advantage of the villages is that they contain a community that is able to cooperate more easily, in fact the difference between smart village and smart city goes beyond the sustainable and digital potential.

Would you like to live in a smart village?

- Una rassegna: Cosa abbiamo studiato in italiano nel 2024?

- 10 proverbi italiani di luglio

- Il fornaio celiaco del Rinascimento | Un racconto italiano

- I massacri delle foibe – Il Giorno del Ricordo

- Estate di San Martino- leggenda e tradizioni

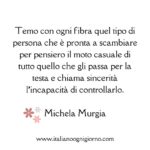

- Michela Murgia: tenace scrittrice e attivista italiana

- I Vini italiani |Storia e Cultura

- Italian Formal and Informal pronouns

- Italian vs. Anglicisms and Gadda -Do we need a law to protect Italian?